There had been rumours throughout Thursday, after the US government announced it was removing non-essential personnel from Iraq and other locations in the region. People were contacting relatives in government and in the Israeli Defence Force (IDF) to ask if this was “the big one” that the populations of Israel and Iran had been waiting for. At 3am on Friday morning people had their answer.

I was woken by air-raid sirens sounding across Tel Aviv, followed shortly after by the alarm in the hotel. An automated voice instructed me to move to the internal missile shelter that nearly every building in the city has. For those caught in the open there are public shelters dotted around.

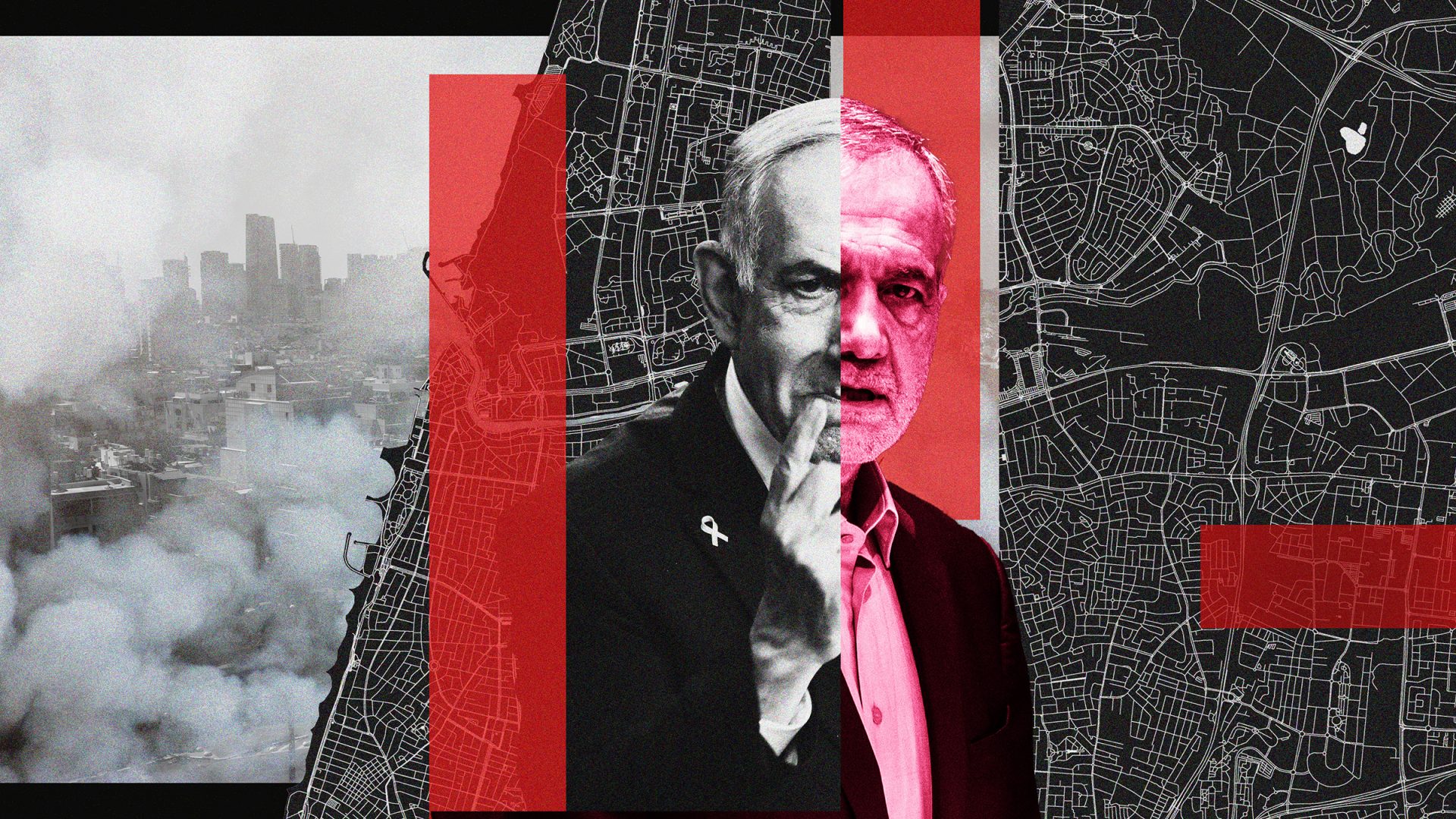

Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, described Israel’s attack on Tehran as “a targeted military operation to roll back the Iranian threat to Israel’s very survival”. The nuclear facility at Natanz was a particular focus. Iranian state TV reported the deaths of six scientists, as well as civilians, including children.

None of the first 100 Iranian drones launched at Israel in retaliation reached their intended targets. Unlike the Iranian drones used by Russia that are being fired at Kyiv in increasing numbers, the majority launched against Israel were intercepted.

Hotel receptions were busier than usual at 5am when the “shelter in place” restrictions put in place by Israel’s home front command were lifted. People were rushing to check out of hotels so that they could leave the city.

I had to stay, as all flights were cancelled – airspace over Israel, Jordan, Iran, Iraq and Syria was shut. El Al removed some of its planes from Ben Gurion airport in Tel Aviv as a precaution, in case the airport was hit.

War’s worst consequence is the severing of connections. There is the temporary separation of people stuck on the wrong side of closed borders, people interned by authorities and people conscripted to do their duty on the battlefield. Then of course there is the separation of death. Recent events will create separations of both kinds.

Walking through Tel Aviv on Friday afternoon there was a veneer of normality. Businesses were open and people were moving around freely. Missile alerts are a fact of life here. They sounded in Tel Aviv on Tuesday as the Houthis fired rockets from Yemen. When the wind blows from the south it is possible to hear explosions from operations in Gaza, 50 miles away. These detonations seem to be largely ignored. The destruction and death they are causing seem a world away from the open air bars and beach-side restaurants.

Suggested Reading

Trump and Netanyahu – two authoritarians in search of a legacy

There is great faith in Israel’s air defences, including its famous Iron Dome system, but complex formations of large numbers of drones and Iranian missiles are a greater test than the Houthis.

Air raids are a unique form of terror: the helplessness of sitting and waiting for an unseen, faceless projectile to land and detonate, with its shards of burning metal and lung-exploding blast wave. Your survival is down to luck. In order to reduce the risk of a nuclear attack, Israel is inflicting precisely this terror on the people of Iran. But in doing so, it has increased the risk that this terror will be visited on its own people.

On Friday evening, the Iranian response came. Throughout the night we were sent back into the shelters to sit and wait and hope we would not be unlucky. We would try to discern whether the muffled explosions we could hear through the walls of the shelter were the sound of Israeli battery fire intercepting incoming projectiles, or direct hits from Iranian missiles and drones. News reports on our phones confirmed it was both, and that there were those elsewhere in the city who had not been as lucky.

But while there are many dissenting voices here about Netanyahu’s handling of the war in Gaza, there is near total support for a war against Iran. Iran’s nuclear programme is seen as an existential threat. The fear is genuine.

Netanyahu has asked for patience as he tries to achieve an objective he has been talking about since the 1990s. He is willing to pay the price of many more nights like Friday night. As the casualties increase, even those who care little for casualties in Iran may start to question if he really is making Israel a safer place.

Sitting in Tel Aviv listening to the bellicose statements of the leaders on both sides of this rapidly escalating war, it is impossible not to think about mortality. Instead of focusing on what technology and weaponry the respective militaries have, I hope more of the participants recognise the relationship of mutual risk they are in.

Now more than ever, we should focus on what everyone in the region has to lose: all of those connections that can be broken, sometimes temporarily, but increasingly and tragically, for ever.

Andy Owen is an author and former intelligence officer in the British army